We are very pleased to share our provisional programme for this year’s GeoForum event on Thursday 28th February 2019 at Lancaster House, Lancaster University, LA1 4GJ. GeoForum is a free all day event aimed at lecturers, researchers and support staff who promote and support the use of geospatial data and services at their institution. Throughout the day […]

Celebrating Robert Burns

Today (25th January) is the anniversary of the birth of the Scottish poet and lyricist Robert Burns (1759-1796). To celebrate this day, we have complied a list of some weird and wonderful titles covering Scottish poetry and literature, both written in English and Scottish Gaelic.

- Effie.

- Things.

- Southfold.

- Fish-sheet.

- Skinklin star.

- Hjok-finnies sanglines.

- Calypso Grampian.

- Storm.

- Dark horse.

- The New alliance.

- The Jabberwock.

- Northwords.

- Poor old tired horse.

- Weighbauk.

- Deliberately thirsty.

- Gutter : the magazine of new Scottish writing.

- Green shoots.

- Out from beneath the boot.

- Sideways.

- Pushing out the boat.

- Splash.

- Riverrun : new writing from Dundee.

- Laldy! : West of Scotland’s literary journal.

- New writing Scotland. 36, With their best clothes on.

For more titles of Scottish poetry and literary collections take a look in SUNCAT.

SUNCAT updated

SUNCAT has been updated. Updates from the following libraries were loaded into the service this week. The dates displayed indicate when files were received by SUNCAT.

- British Library (24 Jan 19)

- Canterbury Christ Church University (19 Jan 19)

- CONSER (Not UK Holdings) (23 Jan 19)

- Cranfield University (20 Jan 19)

- De Montfort University (22 Jan 19)

- Directory of Open Access Journals (18 Jan 19)

- Oxford University (23 Jan 19)

- School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) (21 Jan 19)

- Southampton University (20 Jan 19)

- St. Andrews University (24 Jan 19)

- Trinity College Dublin (17 Jan 19)

- University of the West of England (24 Jan 19)

To check on the currency of other libraries on SUNCAT please check the updates page for further details.

Coastal Erosion examples using Digimap for Schools

We were recently demo’ing some scenarios of how to use the historical maps with current day Ordnance Survey maps and we thought we’d share the maps we created.

This example is of coastal erosion in Happisburgh in Norfolk. By using the historic maps and our drawing and measurement tools you can trace the coastline in the 1890’s, the 1950’s and the current coastline. You can also use the measurement to see that in some areas the coast has eroded about 150 metres..

I ‘think’ in the GCSE and A-Level NEA’s (though don’t quote me! I’m not a teacher  it talks about data presentation and using secondary data sources; and on both fronts Digimap for School more than covers these specifications.

it talks about data presentation and using secondary data sources; and on both fronts Digimap for School more than covers these specifications.

Introducing SUNCAT’s new Contributing Library: the Royal Academy of Dance

We are excited to announce that the Royal Academy of Dance is our newest Contributing library. To tell us more about the organisation, the library and its serial collection, we invited Carlos Garcia Jane, Assistant Librarian, to write a few words.

________________________

The Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) is one of the world’s most influential dance education organisations. Founded in 1920 to set standards for dance teaching within the UK, today we have a presence in 84 countries, with 36 offices and around 14,000 members worldwide. We count more than 1,000 students in our teacher training programmes and more than a quarter of a million students are being examined on our syllabi. Our membership is supported through the knowledge and expertise of RAD’s highly qualified staff and through conferences, workshops, training courses and summer schools. The Faculty of Education is dedicated to meeting the needs of our current and future dance teachers by providing dance teacher education programmes and qualifications. Our exams are recognised by Ofqual and contribute to UCAS points. The RAD’s patron is Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

The Royal Academy of Dance, Battersea, London. (© Royal Academy of Dance.)

The Philip Richardson Library houses one of the largest specialist dance collections in the UK. Based at the RAD Headquarters in Battersea, London, we welcome visitors from around the world as well as RAD members, friends, students and staff. The open access collections include books, CDs, DVDs, conference proceedings, resource packs and Benesh Movement Notation Scores. The dance collection is supplemented by resources in the related fields of pedagogy, music, anatomy and physiology. Materials in the archives and special collections include rare books, theatre programmes, photographs, costume designs, pictures and artifacts, as well as audio-visual materials and paper-based documents and correspondence.

Our expanding collection of serials contains over 170 individual titles, 30 of which are print subscriptions, alongside online resources and databases. The serials collection focuses on dance history and criticism, choreography, dance education and training, and dance medicine and science. The collection includes a complete run of the Dance Gazette, a highly-respected international dance publication, produced by the Royal Academy of Dance since 1930. Among other important serial titles, our collection also features runs of Dancing Times, Dance Magazine, and Dance & Dancers.

Our collection will be beneficial to students, researchers and academic interested in ballet, dance and related topics. Find more information about our collections and activities on our website, our library catalogue, or follow us on twitter @RADLibrary. To arrange a visit contact us on library@rad.org.uk or 02073268032.

______________________

SUNCAT would very much like to thank Carlos for introducing the library and its journal collection. If you would like to write a post on your SUNCAT Contributing Library and its serials collections please contact us at suncat@ed.ac.uk.

Highland Childhoods in the Old Statistical Accounts – Part 1

Guest blog post

It is always wonderful to discover first-hand how people use the Statistical Accounts of Scotland. Two MLitt students of the University of the Highlands and Islands, Helen Barton and Neil Bruce, have carried out research on gender and family in the Highlands using the the Statistical Accounts of Scotland. They have written a blog post, divided into two parts, providing us with the results of their research. Below is part one, covering the themes of health and disease and family structures of children living in the Highlands.

________________________________________

Last year as part of our Masters course, we considered ‘Gender and the Family’ in the Highlands. We were challenged to use the Statistical Accounts to research the experience of childhood. We know very little about children in the region in the pre-Clearance era, and what little we do know is about the offspring of the elite, “the formal education and socialisation of children where it yielded a written record is more easily understood” (S. Nenadic, Lairds and luxury: the Highland gentry in Eighteenth-century Scotland (Edinburgh, 2007), p. 43).

An historian focusing on lost English society, Peter Laslett found the “crowds and crowds of little children … who were a feature of any pre-industrial society” are often missing from the record. Margaret King broadened this point across Europe: “We know less about the course of childhood itself, the socialization of the young, and the lives of the poor, always a black hole” (P. Laslett, The World We Have Lost (London, 1971), pp. 109-110, quoted in H. Cunningham, ‘The Employment and Unemployment of Childhood in England c. 1680-1851’, Past & Present, No. 126 (1990), p. 115; M. L. King, ‘Concepts of Childhood: What We Know and Where We Might Go’, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 60, no. 2 (2007), p. 388).

Sir John Sinclair included three questions relating to children:

- The parish’s school population

- Family sizes

- The number of under-ten-year olds.

With this limited and “unwitting testimony” provided by the authors of the parish reports, the historian can glean an understanding of what children’s lives involved (A. Marwick, The Fundamentals of History, accessed 26th June 2018).

In our research we focused on the Outer Isles, Skye and the Far North, and the themes of

- Health and Disease

- Family Structures

- Work

- Education

We’ll cover the first two sections in this blog and the other two in part two.

Health and Disease

The reports frequently refer to children (and families) having a high risk of contracting and succumbing to disease. Surviving the first five to eight days was crucial in Lewis, where a “complaint called the five night sickness” “prevails over all the island” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 265, p. 281). The minister in Barvas thought “the nature of this uncommon disease … (was not) … yet fully comprehended by the most skilful upon this island” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 265). In Uig, it was described as epilepsy, where, other than two cases, all contracting it died; one survivor experienced severe fits, remaining “in a debilitated state”. Incomers had initial immunity, but even their new-born could contract it (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 281). Croup “proved very mortal, and swept away many children” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 279).

Smallpox had a “calamitous” effect, during an apparent epidemic, 38 children died within months; parents in Tarbat, Easter Ross, were “deaf” to the “legality and expediency” of inoculation (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, pp. 428-429). An epidemic in Harris in 1792 “carried off a number of the children”, most “inoculated by their parents, without medical assistance” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1794, p. 385). In Strath on Skye, and on North Uist, inoculation had “now become so general” that “the poor people, to avoid expenses, inoculate their own children with surprising success” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1793, p. 224; Vol. XIII, 1794 p. 312). In Tongue, in Sutherland, within five years of inoculations being introduced, smallpox had been virtually eradicated (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 524). Even were a doctor affordable, there were only three surgeons and no physicians listed between Skye, the Small Isles, and the Outer Hebrides, all three in the latter, two of whom were on Lewis (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 250; OSA, Vol XIX, 1797, p. 281; OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 613).

Common “distempers” included colds, coughs, erysipelas (a skin infection) and rheumatism (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 275; OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 308; OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 264). The most comprehensive list of diseases was on Small Isles, including ‘hooping’ cough, measles, catarrh, dropsy of the belly, and pleurisy (OSA, 1796, Vol. XVII, p. 279).

It is more difficult to understand from the reports who cared for children when they were ill, or the role children had caring for others, in a community and society where “constant manual labour produced early arthritis … old age came prematurely, without the possibility of retirement for most” (H. M. Dingwall, ‘Illness, Disease and Pain’, in E. Foyster (ed), History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1600 to 1800 (Edinburgh, 2010), p. 114). In rural Sweden, Linda Oja found that both parents had roles in caring for sick offspring (L. Oja, ‘Childcare and Gender in Sweden’, Gender History, Vol. 27, no. 1 (2015), p. 86). Correlating the inter-relationship between diet, health, life expectancy and diseases requires deeper investigation.

Family Structures

The family and work for children of the Highlands and Islands was intertwined. As ordinary daily family life was not the focus of the Accounts’, any details have to be discerned from what they recorded about ‘industry’, wage costs and general passing comments about local living conditions and culture.

Where detailed population statistics were recorded, they demonstrate the average household size. A typical family was nuclear: two adults and four or five children, rising to between seven and 14 in the islands. In many areas, longevity was reported. Women bore children from their early twenties until as late as their fifties, grandmothers were suckling their own grandchildren in the Assynt area (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, pp. 207).

Marriage may have had romantic foundations, but for many was an economic partnership where both partners worked to achieve a living, either waged or unwaged. In Lewis, there was a pragmatic approach to widowhood; “grief … is an affliction little known among the lower class of people here; they remarry after ‘a few weeks, and some only a few days” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, pp. 261-2). Consequentially, children gained step-parents. This claim does seem extraordinary and further investigation through other sources would be beneficial. Nonetheless, the economic hardship of widowhood is well illustrated by his blunt statement.

Families were also on the move in large numbers. The Highlands and Islands were not immune to changes in agricultural systems taking place in the Lowlands and elsewhere. Sir John Sinclair himself was an enthusiastic encourager of new scientific methods. He enclosed his own Caithness estate, changing its management, and introducing new breeds of livestock, including large non-native sheep flocks (M. Bangor-Jones, ‘Sheep farming in Sutherland in the eighteenth century’, Agricultural Historical Review, Vol. 50, no. 2 (2002), pp. 181-202). Many people were displaced to new crofts and settlements on the coast.

The population was declining rapidly in Highland straths, but overall was generally-rising. Couples reportedly married younger than had previously been the trend locally. This was often by the age of twenty, apparently lower than the national average of 26/27 years old. In Halkirk, the report comments on ‘prudential considerations [being] sacrificed to the impulse of nature’ as young people no longer had to wait for an agricultural tenancy (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 23):

Before the period above mentioned, people did not enter early into the conjugal state. The impetus of nature was superseded by motives of interest and convenience. But now, vice versa, these prudential considerations are sacrificed to the impulse of nature which is allowed its full scope; and very young people stretch and extend their necks for the matrimonial noose, before they look about them or make any provisions for that state.

More research on the reasons for earlier marriages would be beneficial.

To be continued …

SUNCAT updated

SUNCAT has been updated. Updates from the following libraries were loaded into the service this week. The dates displayed indicate when files were received by SUNCAT.

- Aberdeen University (05 Jan 19)

- British Museum (04 Jan 19)

- British Library (17 Jan 19)

- Brunel University London (07 Jan 19)

- Canterbury Christ Church University (08 Jan 19)

- CONSER (Not UK Holdings) (16 Jan 19)

- De Montfort University (03 Jan 19)

- Exeter University (05 Jan 19)

- Glasgow University (16 Jan 19)

- Kent University (02 Jan 19)

- London Library (04 Jan 19)

- Manchester Central Library (05 Jan 19)

- Manchester Metropolitan University (15 Jan 19)

- Nottingham University (05 Jan 19)

- Royal Academy of Dance (10 Dec 18)

- Royal College of Music (16 Jan 19)

- Royal Society of Medicine (05 Jan 19)

- Senate House Libraries, University of London (04 Jan 19)

- Southampton University (13 Jan 19)

To check on the currency of other libraries on SUNCAT please check the updates page for further details.

SUNCAT Contributing Libraries: how to get involved with the NBK

Bethan Ruddock, the NBK Project Manager, has written a few words on how the SUNCAT libraries can contribute to the NBK. I hope that you find this useful, and that it encourages you to contact the NBK team, if you haven’t done so already!

I would like to reiterate – as I’m sure that I will be doing a lot over the next few months – that we really appreciate the work that our Contributing Libraries have put into sending us data over the years. SUNCAT would be nothing without the libraries, and their enthusiasm. May this carry on with contributions to the NBK!

Bethan says:

The Jisc National Bibliographic Knowledgebase (NBK) is a project to aggregate bibliographic data at scale and link with a number of other data sources to inform library collection management decisions and to help users more effective find, access and use print and digital scholarly resources.

The NBK data will support 3 main services: resource discovery, collection management, and catalogue record download. The resource discovery service with take over from the current Copac and SUNCAT services at the end of July 2019.

To ensure continued excellent coverage of UK serials holdings as established by SUNCAT, we would like to invite and encourage all current SUNCAT contributors to contribute their data to the NBK. This invitation isn’t limited to serial holdings: we’d be very pleased to get full catalogues from you. For SUNCAT contributors, we are offering the option of sending an initial contribution of serial holdings, allowing you time to consider sending your full holdings later.

More information on contributing can be found at https://contribute.copac.jisc.ac.uk/documentation/ (login with Shibboleth / Open Athens, or contact nbk.copac@jisc.ac.uk to request access). If you have any questions about the NBK, or would like to arrange to contribute, we’d be very pleased to hear from you at nbk.copac@jisc.ac.uk.

SUNCAT updated

SUNCAT has been updated. Updates from the following libraries were loaded into the service this week. The dates displayed indicate when files were received by SUNCAT.

- Aberystwyth University (01 Jan 19)

- Bath University (01 Jan 19)

- Brunel University London (27 Dec 19)

- Cardiff University (01 Jan 19)

- CONSER (Not UK Holdings) (09 Jan 19)

- De Montfort University (21 Dec 18)

- Dundee University (01 Jan 19)

- Durham University (03 Jan 19)

- Edinburgh Napier University (01 Jan 19)

- Imperial College London (01 Jan 19)

- Kingston University (01 Jan 19)

- Lancaster University (01 Jan 19)

- Leeds University (21 Dec 18)

- Leicester University (01 Jan 19)

- London Metropolitan University (21 Dec 18)

- London School of Economics and Political Science (01 Jan 19)

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (01 Jan 19)

- Manchester University (01 Jan 19)

- National Archives (01 Jan 19)

- National Library of Wales (01 Jan 19)

- Natural History Museum (01 Jan 19)

- Northumbria University (01 Jan 19)

- Open University (01 Jan 19)

- Oxford University (23 Dec 18)

- Sheffield Hallam University (01 Jan 19)

- Sheffield University (01 Jan 19)

- Southampton University (30 Dec 18)

- Strathclyde University (01 Jan 19)

- Sussex University (01 Jan 19)

- Swansea University (01 Jan 19)

- University of Wales Trinity Saint David (01 Jan 19)

- University of the West of England (24 Dec 18)

- Warwick University (03 Jan 19)

- York University (01 Jan 19)

To check on the currency of other libraries on SUNCAT please check the updates page for further details.

Crime and punishment in late 18th-early 19th century Scotland: Causes of crime and crime prevention

This is the second in our series of posts on crime and punishment in 18th-19th century Scotland. This time we are looking at what the parish reporters thought were the causes of crime, as well as what measures were being put in place help prevent crime. There are some very interesting opinions on both these subjects found in the Statistical Accounts.

Reasons for crime

- Alcohol

It is not surprising to read that crime was mostly attributed to alcohol, or, more specifically, drunkenness! There are some very damning views shared in the parish reports. The Rev. Mr Thomas Martin wrote in the parish report for Langholm, County of Dumfries, “let the distilleries then, those contaminating fountains, from whence such poisonous streams issue, be, if not wholly, at least in a great measure, prohibited; annihilate unlicensed tippling-houses and dram-shops, those haunts of vice, those seminaries of wickedness, where the young of both sexes are early seduced from the paths of innocence and virtue, and from whence they may too often date their dreadful doom, when, instead of”running the fair career of life” with credit to themselves, and advantage to society, they are immolated on the altar of public justice.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 605)

In Tinwald and Trailflat, County of Dumfries, it was reported that “there are at present 2 small dram-shops in the parish which we have the prospect of soon getting rid of. They have the worst possible effect upon the morals of the people: and there is scarcely a crime brought before a court that has not originated in, or been somehow connected with, one of these nests of iniquity.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 50)

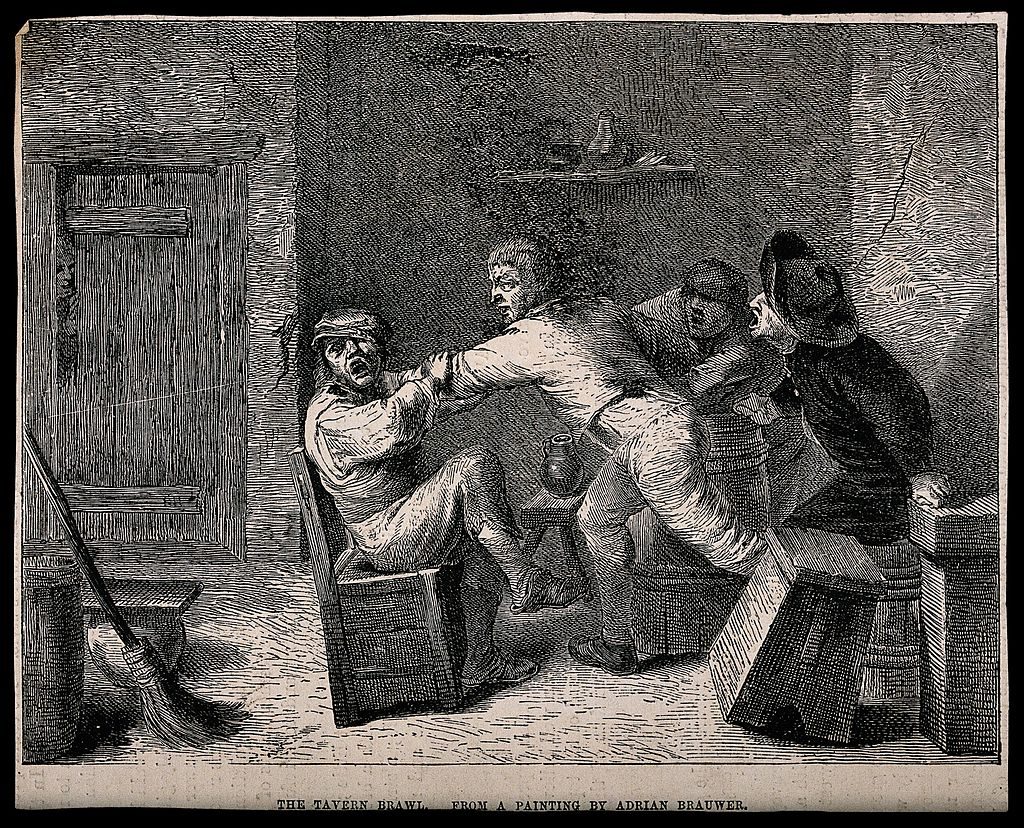

‘A drunken brawl in a tavern with men shouting encouragement’, 19th century wood engraving after A. Brouwer. [Wellcome Images, [CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]

In Stirling, County of Stirling, “there are 96 of these [inns, ale-houses, etc], of different degrees of respectability in the parish ; of which 91 are in the town, and 5 in the villages of Raploch and Abbey.” Two interesting points were also made here: that owners of houses received higher rents if their buildings became ale-houses and that “the number of charitable institutions on which so large a portion of the people have a claim” had a negative impact, as they trained “them to a species of pauperism”. (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 448).

The cheap cost of alcohol, as well as the number of ale-houses in existence, was believed to be a factor in the higher level of crime. In the parish of Orwell, County of Kinross, “in consequence of the low price of spirits within these last six or eight years, there have been more petty crime and drunkenness than was formerly known.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 66)

It is fascinating to read the parish report from Hutton and Corrie, County of Dumfries, which states that “in 1834, the House of Commons appointed a Select Committee of their number to take evidence on the vice of drunkenness. The witnesses ascribe a large proportion, much more than the half of the poverty, disease, and misery of the kingdom, to this vice. Nine-tenths of the crimes committed are considered by them as originating in drunkenness… The pecuniary loss to the nation from this vice, on viewing the subject in all its bearings, is estimated by the committee, in their report to the House of Commons, as little short of fifty millions per annum. ” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 550)

- Itinerant workers

In the parish of Corstorphine, County of Edinburgh, “the persons there employed are collected from all the manufacturing towns in England, Ireland, and Scotland. They are continually fluctuating; feel no degree of interest in the prosperity of the place; and act as if delivered from all the restraints of decency and decorum. In general, they manifest a total disregard to character, and indulge in every vice which opportunity enables them to perform” and is further noted that “the influence of their contagious example must spread” to others in the parish. (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 461)

- Lack of religious upbringing and instruction

In some corners, crime was also attributed to a lack of religious upbringing and instruction. As mentioned above, there was a report made to the House of Commons on drunkenness and its affect on crime. “In London, Manchester, Liverpool, Dublin, Glasgow, and all the large towns through the kingdom, the Sabbath, instead of being set apart to the service of God, is made by hundreds of thousands a high festival of dissipation, rioting, and profligacy.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 550)

Govan, County of Lanark, was seen as a district “where there is no civil magistrate to enforce subordination, and to punish crimes, what can be expected, but that the children should have been neglected in their education; that many of the youth should be unacquainted with the principles of religion, and dissolute in their morals; and that licentious cabal should too often usurp the place of peaceable and sober deportment.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 295) It was also noted that “if neighbouring justices were, at stated intervals, to hold regular courts in so large villages, they might essentially promote the best interests of their country. They would be a terror to evil doers, and a protection to all that do well.”

In the parish report for Ardrossan, County of Ayrshire, it was remarked that “we have certainly too many among us who have cast off all fear of God, and yield themselves up to the practice of wickedness in some of its most degrading forms, yet the people in general are sober and industrious, and distinguished for a regard to religion and its ordinances. Not only is the form of godliness kept up, but its power appears to be felt, by not a few among them maintaining a conversation becoming the gospel.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 199)

Crime prevention

So, according to the parishes throughout Scotland, how best could crimes be prevented? As the parish report of Langholm, County of Dumfries, mentions, “it is much more congenial to the feelings of every humane and benevolent magistrate to prevent crimes by all possible means, than to punish them… Remove the cause, and the effects in time will cease.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 605) In the parish report of North Knapdale, County of Argyle, correcting criminal behaviour is preferable to punishment. “Such evil consequences can never be prevented without knowledge and education; and for this reason men, in power and authority, should pay particular attention to the subject.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 265)

In some quarters, punishments were considered too lenient. In the parish of Fetlar and North Yell, County of Shetland, “the punishments inflicted for such crime of theft, in particular, are so extremely mild, that they rather excite to the commission of the crime than deter from it.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 285) In some parishes trouble-makers and criminals were simply expelled from that city, town or parish, instead of being punished! As pointed out in the parish report of Muirkirk, County of Ayrshire, “this is neither more nor less, than to punish the adjacent country for sins committed in the town, to lay it under contribution for the convenience of the city, and free the one of nuisances by sending them to the other.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 609) (Although in the parish of Killin, County of Perth, “the turbulent and irregular [were] expelled the country to which they were so much attached, that it was reckoned no small punishment by them.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 384))

In Liberton, County of Edinburgh, it was felt that “nothing can remove the evil of assessments now, (which would be ten times greater, but for the efforts of the kirk-session,) but the subdivision of parishes, the diffusion of sound instruction and Christian principle amongst the people, and the removal of whisky-shops. Crime, drunkenness and poverty are always found together, and expending money upon the poor, except for the purpose of making them better, will as soon cure the evil as pouring oil upon a flame will quench it.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 27)

In the parish reports there is no lack of suggestions on how to deter crime and punish criminals.

- Suggestions

– Restrictions on selling alcohol

A very interesting suggestion was made in the parish report for Callander, County of Perth in November 1837. ” Considerable improvement has taken place within these few years in the management of the police of the country; yet there are many crimes allowed to pass with impunity. Would it not tend much to diminish crime if there were fewer licenses granted for selling, spirits, and more attention paid to the character of the persons to whom licenses are given?” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 360) A similar observation is made in the report for the parish of Stirling, County of Stirling, where “granting of licenses, without sufficient inquiry as to the character of the applicant” is believed to be one of the reasons for crime. (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 448)

In the report made to the House of Commons on drunkenness and its affect on crime “a great many of the witnesses recommended the prohibition of distillation, as well as of the importation of spirits into the kingdom.” The report also stated that religious institutions had a big part to play in “rooting out drunkenness, now appearing in every part of the kingdom”. (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 550)

In Kennoway, County of Fife, “the grand remedy, if it could be applied, would be to lay a restriction on the improper use of ardent spirits. Drunkenness is certainly the prevailing vice amongst us ; and is the originator, or at least inciting cause, to almost every mischief. Imprisonment for violent assault under its influence has of late been in two instances inflicted.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 381)

– Law enforcement and confinement

In the parish of Gargunnock, County of Stirling, a problem with vagrants is reported. “They spend everything they receive at the first ale-house; and for the rest of the day they become a public nuisance. The constables are called, who see them out of the parish; but this does not operate as a punishment, while they are still at liberty. It would be of great advantage, if in every parish, there was some place of confinement for people of this description, to keep them in awe, when they might be inclined to disturb the peace of the town, or of the neighbourhood.” (OSA, Vol. XVIII, 1796, p. 114)

The parish of Carluke, County of Lanark, reports specific measures taken against vagrancy. “The inconvenience and loss by acts of theft, etc. which many sustain by encouraging the vagrant poor of

other parishes, we have endeavoured to prevent here, not only by making liberal provision for the poor of this parish, and restraining them from strolling, under the penalty of a forfeiture of their allowance; but also by following out strictly the rule of St. Paul, “If any would not work, neither should he eat.” (2 Thess. iii. 10.) and the laws of our country with respect to idle vagrants.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 140)

Some parishes did not have any sort of, or very little, law enforcement in place.

Drymen, County of Stirling – “There is not a justice of peace, nor magistrate of any kind resident within the bounds of this parish neither is there a jail or lock-up house from the most westerly verge of the county onward to Stirling,–a distance of nearly fifty miles. The consequence is, that crime and misdemeanor frequently go unpunished, the arm of the law not being long enough nor strong enough to reach so far.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 114)

Stromness, County of Orkney – “There is no prison in Stromness. This greatly weakens the authority of the magistrates, and is unfavourable to the morals of this populous district. Were an efficient jail erected, it would intimidate the lawless, and be an effectual means of preventing crime, and the lesser delinquencies.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 38)

Thurso, County of Caithness – “at present the smallest misdemeanor cannot be punished by imprisonment, without sending the offender to the county jail of Wick, at the distance of 20 miles from Thurso, which necessarily occasions a heavy expense to the prosecutor, public or private, and, of course, is the cause of many offences passing with impunity, which would otherwise meet their due punishment.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 545)

Langholm, County of Dumfries – “Instead of banishing delinquents from a town or county for a limited time… would it not tend more to reclaim them from vice, to have a bridewell, upon a small scale, built at the united expense of the 5 parishes, where they could be confined at hard labour and solitary confinement, for a period proportioned to their crimes… The dread of solitary confinement, and the shame of being thus exposed in a district where they are known, would operate in many instances as a powerful preventive.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 613)

Kilmaurs, County of Ayrshire – “Two bailies are chosen annually, but their influence is inconsiderable, having no constables to assist in the execution of their authority; the disorderly and riotous therefore laugh at their threatened punishments.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 370)

Employers and proprietors also had a role to play in deterring crime.

Kilfinichen and Kilviceuen, County of Argyle – “The Duke of Argyll, upon being informed of this complaint, gave orders to his chamberlain to intimate to his Grace’s tenants, and all the kelp manufacturers upon his estate, that whoever was found guilty of adulterating the kelp, would find no shelter upon his estate, and that they would be prosecuted and punished as far as the law would admit. This will have a good effect upon his Grace’s estate, and is worthy of imitation by the Highland proprietors of kelp shores.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 182)

St Cyrus, County of Kincardine – “poaching for game has become much less common of late years, from the active measures employed by a game-association, instituted among the principal landed gentlemen of the county, for the punishment of this species of delinquency.”(NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 286)

- Increased religious instruction/services – spiritual and moral improvement

In Langton, County of Berwick, there were parochial visitations when there was discussion about any issues affecting the congregation between the presbytery and the elders, and then the congregation itself. “It is impossible to conceive a system more fitted to promote the diligence and faithfulness of ministers, or the spiritual and moral improvement of parishes. Its effects, accordingly, were visible in a diminution of crime, and an increase of personal and family religion among the surrounding districts.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 244)

In Hamilton, County of Lanark, “much has been said of the happy influence of Sunday schools in other places. If there were people of wealth and influence heartily disposed to strengthen virtue, to encourage good behavior, and to discountenance vice and irregularity, by establishing that institution here, in order to rescue the children of dissolute parents, from the danger of bad habits, to instruct them in the principles of religion, and a course of sobriety and industry, it is probable, they might be the happy means of restoring and improving the morals of all the people in this populous district.” (OSA, Vol. II, 1792, p. 201)

An interesting observation is made in the parish report of Hawick, County of Roxburgh. “The cases of gross immorality which occurred during the course of about thirty years before the Revolution, and when Episcopacy was predominant, were about double the number that took place during the course of thirty years after it, and when Presbytery was restored, which may justify the conclusion, that the exercise of discipline according to the constitution of the Church of Scotland is of signal efficacy in restraining the excesses of profligacy and crime.” (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 392)

- Better street lighting

In Edinburgh, County of Edinburgh, “the frequent robberies and disorders in the town by night occasioned the town-council to order lanterns or bowets to be hung out in the streets and closes, by such persons and in such places as the magistrates should appoint,–to continue burning for the space of four hours, that is, from five o’clock in the evening till nine, which was deemed a proper time for people to retire to their houses.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 627)

Better street lighting was also identified as a form of crime deterrent in Dundee, County of Forfar. “In consequence of the rapid increase of the population of Dundee and surrounding district, and the ordinary provision of the law for preserving the public peace having become inadequate for the purpose, in 1824, the magistrates, with the concurrence of the inhabitants at large, applied to Parliament for an act to provide for the better paving, lighting, watching, and cleansing, the burgh, and for building and maintaining a Bridewell there… The police establishment has been of essential service to the inhabitants, with respect to the protection of their persons and property; although it cannot be denied that the streets are not much improved. The number of watchmen is too limited for the extent of the bounds, and the suburbs, which are generally haunts of the disorderly, are but poorly lighted.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 8)

________________________________

Conclusion

Writers of the parish reports had very clear opinions on the causes of crime and ways to tackle it. Alcohol and the resulting drunkenness was by far and away the most cited cause. It was deemed such a problem that, in 1834, the House of Commons appointed a Select Committee to investigate and report on ‘the vice of drunkenness’. some also blamed the lack of religious upbringing and moral and spiritual standards. As pointed out in our last blog post, a number of parishes reported that their citizens as, in the main, law-abiding, using such words as honest, sober, industrious, religious and moral. With regards to crime prevention, many parishes reported that the criminal system needed improving, including the building of bridewells and prisons, and the increasing of law enforcement. Specific measures against the licensing to sell alcohol and the cheap pricing of alcohol were also suggested. All this information that we find in the Statistical Accounts provides us with a fascinating insight into crime and its causes at that particular time. It allows us to think about how the causes of crime and preventative measures have changed (or stayed the same!) since the late eighteenth – early nineteenth centuries.

In our next post we will be looking at different types of punishment handed out to criminals in eighteenth and nineteenth century Scotland and how this correlates to the types of crime committed.