In our last two blog posts in our series on crime and punishment we have looked at levels, types, causes and prevention of crime. But, how exactly did parishes in late 18th – early 19th century Scotland, and even earlier, punish offenders? It wasn’t just a matter of throwing people into prison. As we have found out in the last post, some parishes did not even have a bridewell or prison. Also, what was the correlation between the type of crime and type of punishment? We will find out in this post.

Punishments

It is fascinating to discover some of the crimes and resulting punishments detailed in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland. Examples include: in Leochel, County of Aberdeen, “breaking and destroying young trees in the churchyard of Lochell, [a fine of] one merk for each tree; letting cattle into mosses and breaking peats, 40S.; beating, bruising, blooding and wounding, L. 50;… putting fire to a neighbour’s door, and calling his wife and mother witches, L. 100… ” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 1125) and in Paisley, County of Renfrew, “1606, May 18.-Three vagabonds are ordered to be “carted through the street and the cart;” with certification that if they return, they shall be “scourged and burnt,” ie. we presume, branded on the cheek;… 1622, June 13.-Two women accuse one another of mutual scolding and “cuffing;” the one is fined 40s. the other is banished the burgh, under certification of “scouraging,” and “the joggs” if she returned… 1642, 24 January.-“No houses to be let to persons excommunicated and none to entertain them in their houses, under a pain of ten punds… ” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 182)

It was noted in the parish report of Glasgow, County of Lanark, that all the punishments given by the kirk session in Glasgow, whether it was “imprisoning or banishing serious delinquents, or sending them to the pillory, or requiring them to appear several Sabbath days in succession at the church-door in sackcloth, bare-headed and bare-footed, or ducking them in the Clyde,… no rank, however exalted, was spared, and that a special severity was exercised toward ministers and elders and office-bearers in the church when they offended. There was no favouritism.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 932)

Below we look more closely at punishments for particular crimes, many from times before the Statistical Accounts of Scotland.

- Punishment for adulterers

On the 16th August 1587, a Kirk session in the parish of Glasgow, County of Lanark, “appointed harlots to be carted through the town, ducked in Clyde, and put in the jugs at the cross, on a market day. The punishment for adultery was to appear six Sabbaths on the cockstool at the pillar, bare-footed and, bare-legged, in sackcloth, then to be carted through the town, and ducked in Clyde from a pulley fixed on the bridge.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 110) You can also read here, in the parish report for Glasgow, County of Lanark, what the punishment was for “a man excommunicated for relapse in adultery”, which involved being “bare-footed, and bare-legged, in sackcloth, with a white wand in his hand”!

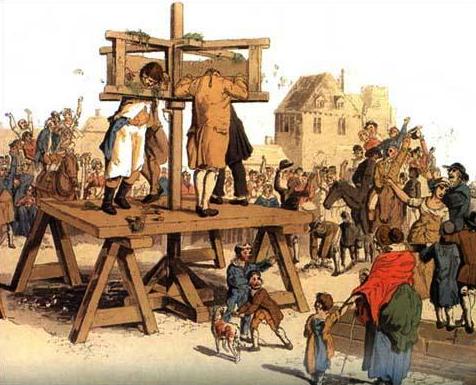

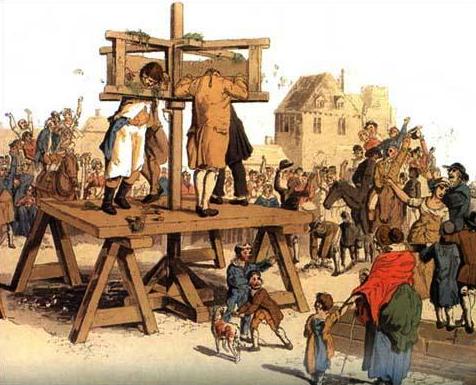

William Pyne: The Costume of Great Britain (1805) – The Pillory. [Picture via Wikimedia Commons.]

As mentioned in the appendix for Edinburgh, County of Edinburgh, “in 1763-The breach of the seventh commandment was punished by fine and church-censure. Any instance of conjugal infidelity in a woman would have banished her irretrievably from society, and her company would have been rejected even by men who paid any regard to their character. In 1783-Although the law punishing adultery with death was unrepealed, yet church-censure was disused, and separations and divorces were become frequent, and have since increased. Women, who had been rendered infamous by public divorce, had been, by some people of fashion, again received into society, notwithstanding the endeavours of our worthy Queen to check such a violation of morality, decency, the laws of the country, and the rights of the virtuous. This however, has not been recently attempted.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 611)

Punishment for witchcraft

There are several reports on witchcraft trials and punishments in the Statistical Accounts, a chapter of Scottish history which, by the late 18th-early 19th century, was seen as a disgrace. As noted in the parish report of Dalry, County of Ayrshire, “this parish was the scene of one of those revolting acts which disgrace the annals of Scotland, of condemning persons to the flames for the imputed crimes of sorcery and witch-craft. This case, which is allowed to be the most extraordinary on record, occurred in 1576. Elizabeth or Bessie Dunlop, spouse of Andrew Jack in Linn, was arraigned before the High Court of Justiciary, accused of sorcery, witchcraft, &c.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 217)

During the 1590s, “the crime of witchcraft was supposed to be prevalent in Aberdeen as well as in other parts of the kingdom, and many poor old women were sacrificed to appease the terrors which the belief in it was calculated to excite. Few of the individuals who were suspected were allowed to escape from the hands of their persecutors; several died in prison in consequence of the tortures inflicted on them, and, during the years 1596-97, no fewer than 22 were burnt at the Castlehill.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 21)

In Erskine, County of Renfrew, “these unhappy creatures, (who seem by their own confession to have borne no good character,) were brought to trial at Paisley in the year 1697, and after a solemn inquest, they were found guilty of the crime of witchcraft, and sentenced to be burnt alive, which sentence was carried into effect at the Gallow Green of Paisley on Thursday the 10th June 1697, in the following manner: They were first hanged for a few minutes, and then cut down and put into a fire prepared for them, into which a barrel of tar was put, in order to consume them more rapidly.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 507) For more information on the crime of witchcraft read our blog post “Wicked Witches“.

Punishment for other crimes

You can find many more examples of punishments for a number of different crimes in the Statistical Accounts. In Blantyre, County of Lanark, “any worker known to be guilty of irregularities of moral conduct is instantly discharged, and poaching game or salmon meets with the same punishment.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 324) In Nairn, County of Nairn, “unfortunately, however, this spring two lads were tried and condemned at Inverness for shop-breaking and theft. One of them was hanged. It is surely much to be wished that his fate may prove a warning to others, to avoid the like crimes. The other young man (brother to the lad who was executed), has been reprieved” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 392)

There are also some particular, infamous crimes reported in the parish accounts, including that of Maggy Dickson in the parish report of Inveresk, County of Edinburgh. “No person has been convicted of a capital felony since the year 1728, when the famous Maggy Dickson was condemned and executed for child-murder in the Grass-market of Edinburgh, and was restored to life in a cart, on her way to Musselburgh to be buried. Her husband had been absent for a year, working in the keels at Newcastle, when Maggy fell with child, and to conceal her shame, was tempted to put it to death. She kept an ale-house in a neighbouing parish for many years after she came to life again, which was much resorted to from curiosity. But Margaret, in spite of her narrow escape, was not reformed, according to the account given by her contemporaries, but lived, and died again, in profligacy.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 34)

Many of the examples of punishments are actually from previous times of the Statistical Accounts, and, as for those for witchcraft, were by the time of the Statistical Accounts seen as barbaric. In the parish report for Campbelton, County of Argyle, it is noted that “five or six centuries seem to have made no change in manners, under the later Kings, or their successors, the Macdonalds; as we find the most barbarous punishments inflicted on criminals and prisoners of war such as putting out their eyes, and depriving them, of some other members.” (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 542)

Castle Campbell – general view form the north east. [Photo credit: Tom Parnell [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons]

A great story illustrating the kind of punishment being imposed in times gone by is that of Castle Campbell, also known as the Castle of Doom, situated in the parish of Dollar, County of Clackmannan. “Tradition, indeed, which wishes to inform us of every thing, reports, that it was so called from the following circumstance: A daughter of one of our Scotch Kings, who then resided at Dunfermline, happening to fall into disgrace for some improper behaviour, was, by way of punishment, sent and confined in this castle; and she, (not relishing her situation, which probably might be in some vault or other) said, that it was a gloomy prison to her. Hence, says tradition, it came to be called the Castle of Gloom.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 167) In fact, “while confined there, she gave names to certain places and streams adjoining the eastie, corresponding to the depressed state of her mind at the time. The place of her confinement she called Castle Gloom. The hill on the east of the castle she called Gloom hill, which name it still retains. to the two streamers which glide by on the east and west sides of the knoll on which the Castle is built, she gave the names of the burns of Care and Sorrow.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 76)

More evidence of such a punishment can be found at Fyvie Castle, County of Aberdeen.”The south wing has in front a tower called the Seton tower, with the arms of that family cut in freestone over the gate. The old iron door still remains, consisting of huge interlacing bars, fastened by immense iron bolts drawn out of the wall on either side; and in the centre of the arch above the door-way, a large aperture called the “murder hole,” speaks plainly of the warm reception which unbidden guests had in former times to expect.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 331)

Instruments of Punishment

As not all parishes, or even counties, had a bridewell or prison, instruments of punishment were being used, especially before the days of the Statistical Accounts. It had the added advantage of acting as a deterrent – making the punishment very public and, therefore, humiliating.

Jougs

Jougs are “an instrument of punishment or public ignominy consisting of a hinged iron collar attached by a chain to a wall or post and locked round the neck of the offender” as defined by the Scottish National Dictionary (1700-) found on the Dictionary of the Scots Language website. (Incidentally, this is a great resource to use if you come across words you don’t understand in the Statistical Accounts!)

In the parish report of Dunning, County of Perth, “there is no jail, but in lieu of it there is that old-fashioned instrument of punishment called the jougs.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 722) The jougs in Marykirk, County of Kincardine, were to be found “on the outside of the church, strongly fixed to the wall.” Interestingly, “these were never appropriated by the church, as instruments of punishment and disgrace; but were made use of, when the weekly market and annual fair flood, to confine, and punish those who had broken the peace, or used too much freedom with the property of others. The stocks were used for the feet, and the joggs for the neck of the offender, in which he was confined, at least, during the time of the fair.” (OSA, Vol. XVIII, 1796, p. 612)

Jougs at Duddingston Kirk. Kim Traynor [CC BY-SA 3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

In Yester, County of Haddington, the jougs were “fastened round neck of the culprit, and attached to an upright post, which still stands in the centre of the village, and is used for weighing goods at the fairs. Here the culprit stood in a sort of pillory, exposed to the taunts and missiles of the villagers.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 166)

Similarly, jougs were described in the parish report of Ratho, County of Edinburgh. “This collar was, it is supposed, in feudal times, put upon the necks of criminals, who were thus kept standing in a pillory as a punishment for petty delinquencies. It would not be necessary in such cases, we presume, to attach to the prisoner any label descriptive of his crime. In a small country village the crime and the cause, of punishment would in a very short time be sufficiently public. Possibly, however, for the benefit of the casual passenger, the plan of the Highland laird might be sometimes adopted, who adjudged an individual for stealing turnips to stand at the church-door with a large turnip fixed to his button-hole.* The jougs are now in the possession of James Craig, Esq. Ludgate Lodge, Ratho. * Since writing the above, we find that the jougs were originally attached to the church, and were used in cases of ecclesiastical discipline.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 92)

In the parish report for Monzie, County of Perth the jougs belonged “to the old church of Monzie, taken down in 1830” and was described as thus: “It was simply an iron collar, fastened to the outside of the wall, near one of the doors, by a chain. No person alive, it is believed, has seen this pillory put in requisition; nor is it known at what period it was first adopted for the reformation of offenders; but there can be no doubt, that an age which could sanction burning for witchcraft, would see frequent occasion for this milder punishment. It is now regarded as a relic of a barbarous age, and has been affixed to the wall of the present church merely to gratify the curiosity of antiquaries.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 270)

The jougs in Dunkeld, Country of Perth, were not, as per usual, attached to the the church but to the old cross. “The old cross was a round pillar, on which was four round balls, supporting a pyramidal top. It was of stone, and stood about 20 feet high. The pedestal was 12 feet square. On the pillar hung four iron jugs for punishing petty offenders. The cross was removed about forty years ago.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 979)

Branks

In the parish report of Langholm, County of Dumfries, you can find a description of branks. “This was an instrument of punishment kept by the chief magistrate, for restraining the tongue. The branks was in the form of a head-piece, that opens and incloses the head of the culprit,–while an iron, sharp as a chisel, enters the mouth and subdues the more dreadful weapon within. Dr Plot, the learned historian of Staffordshire, has given a minute description and figure of this instrument; and adds, that he looks upon it ” as much to be preferred to the ducking-stool, which not only endangers the health of the party, but also gives the tongue liberty ‘twixt every dip, to neither of which this is at all liable.” When husbands unfortunately happened to have scolding wives, they subjected the heads of the offenders to this instrument, and led them through the town exposed to the ridicule of the people”. (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 421)

Conclusion

As can be seen from reading this and the previous posts, the Statistical Accounts of Scotland contains a wealth of information on crime and punishment. Many parish reports describe the crimes and subsequent punishments from olden times, sometimes showing a sense of disgust at their barbarous, unjust nature. In some instances, there are even physical reminders, with there being instruments of punishment still in the parish. This all illustrates how changes are made continually and how, by looking back, you can discover how far we have come.