In October 1795, Sir John Sinclair asked Rev. Robert Douglas of Galashiels to “assist the Board of Agriculture� by updating and republishing the County Surveys of Roxburghshire and Selkirkshire. Sinclair had been frustrated at the eccentric diversity of styles employed by the various contributors to the first phase of the Statistical Account, and he now sought to standardise according to the model of his favourite: the Midlothian survey. He hoped that Douglas would contribute his local knowledge to a national statistical survey, by copying the format, structure, and style of a prototype. However, the production of this survey, and in particular the production of the map it contained, illustrates just how challenging such standardisation could be.

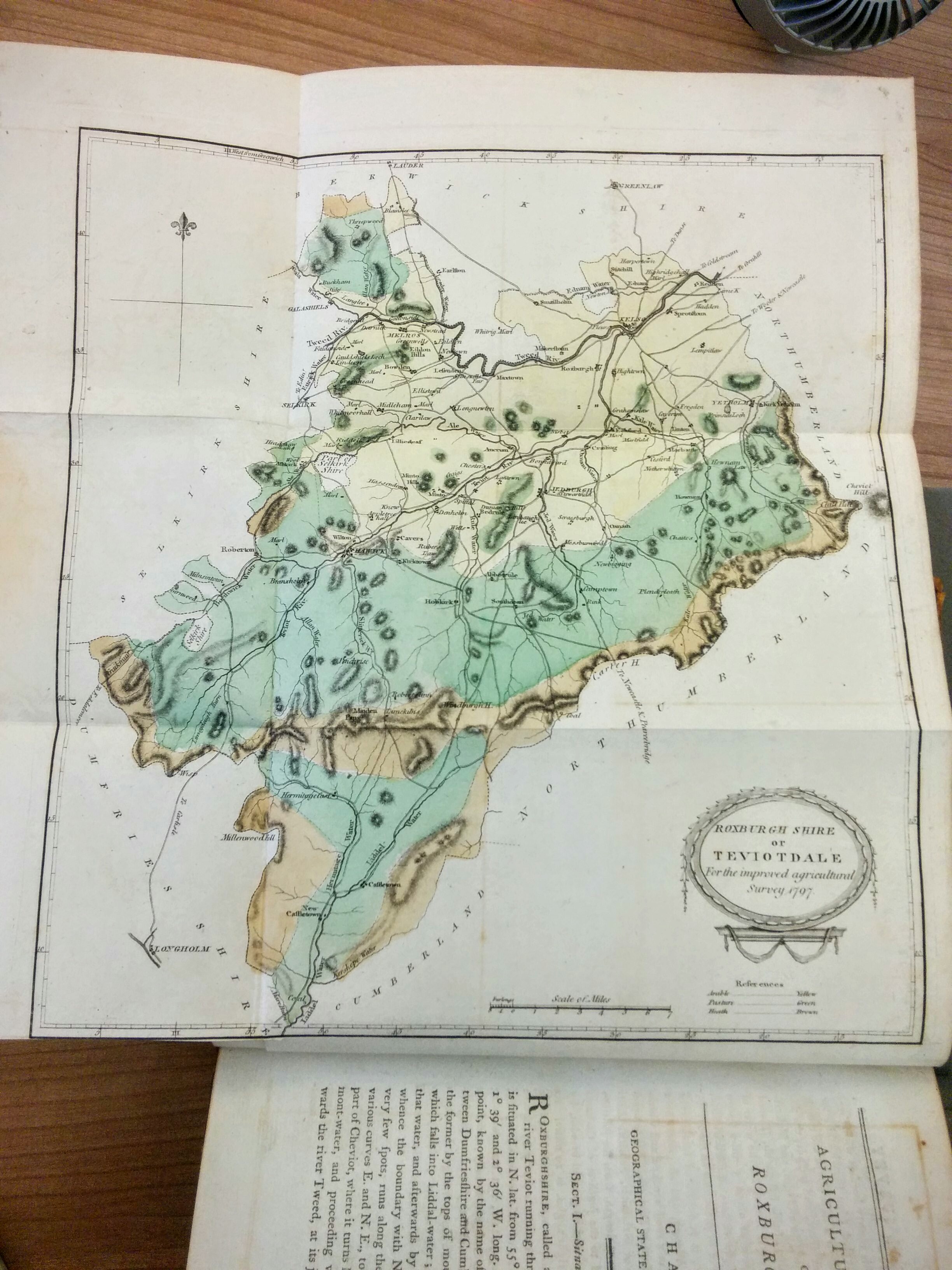

Map of Roxburghshire, from the General View of the Agriculture in the Counties of Roxburgh and Selkirk (1798). Photo by the author.

By January 1798, Douglas’s reports were completed and published, alongside a map of each county, in a single volume: General View of the Agriculture in the Counties of Roxburgh and Selkirk, with Observations on the Means of Their Improvement. To produce the maps, Douglas engaged the professional assistance of the Edinburgh-based mapmaker John Ainslie. Ainslie has been called “virtually the Master-General of Scotland’s national survey�. He was employed to prepare maps of a number of Scotland’s southern counties, at the indirect behest of Sinclair, to illustrate the various Surveys in the late 1790s. In some cases, where the county had already been surveyed in recent decades, Ainslie’s task was merely to copy pre-existing maps. In the case of Roxburghshire, Ainslie used a pantographer to reduce Matthew Stobie’s 1770 map of the county. Ainslie wrote to Douglas in May 1797:

I have perused the coloured map of the County [of Roxburghshire] and has [sic] begun Engraving a new Plate by reducing Stobies map exactly and have put in the villages and Towns from the map you sent onto me. I am at the greatest loss about the Hills. You complain of them being too dark, if I had done them for another county they would have been reckoned too light. I am doing the County of Kirkudbright just now and the people concern’d about it finds great fault because the hills are not dark enough altho much bolder than your map they have actually given me orders to make every one of them stronger before I get them done as they want they will be very dark indeed.

So Ainslie had trouble standardising the topographical features on his county maps, as he found that different counties’ hills required different treatment. In the same letter he refers to the map of Selkirkshire as “totally hills which is the most tedious of all engraving�.

In the preface of his General View, Douglas felt obliged to explain the different cartographic rationales that informed the maps of Roxburghshire and Selkirkshire:

In that [map] of Roxburghshire, nothing is inserted, but the names of parishes, towns, villages, such places as are mentioned in the work, and a few on the confines which jut out into other counties. With regard to Selkirkshire, there being few parish churches or villages, and not many farms deserving particular notice in an agricultural view, had the same rule been rigidly followed, a large track of it would have appeared uninhabited; to prevent which, the seats of the residing proprietors, the places from whence others take their titles, and some of the most extensive farms, are named in the map

In some cases, the imperfect science of hill-mapping led to debates about a hill’s very existence. Douglas had sought advice about possible “alterations and additions� to Ainslie’s draft map of Roxburghshire. He sent a manuscript copy to a number of correspondents, who took it out into the field to test its accuracy. James Arkle, minister for Castletown in the southern tip of Roxburghshire, wrote to Douglas with his own opinions on Ainslie’s map:

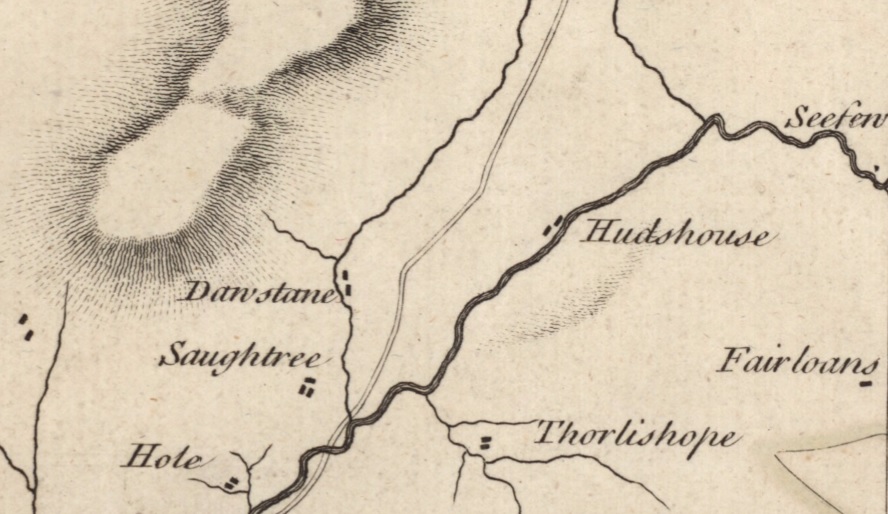

I received yours with the Map of the County inclosed which I now return and shall with pleasure give such answers to your enquiries as my information enables me… I have… carried the map along with me thro’ the parish and have compared it with the real situation of the Country by occular [sic] inspection. The line is drawn with ink separating the moor from the green pasture as accurately as possible. We are not of Mr Olivers opinion as to the nonexistence of the hill he has crossed. It lies between Thorlishope and Peel, tho’ not high when compared with the others near it, yet it rises to a considerable height. I cannot say that I am able to mark the hills by name as they appear on your map. If you have a copy of Stobies Map of County, I believe they are distinctly pointed out on it.

“Mr Oliver� had been given first look at Ainslie’s map, which was a reduced version of Stobie’s, and had crossed out a hill. Clearly Arkle disagreed with his assessment, on the basis of his own subjective “occular inspection.� The hill in question lay northeast of Thorlishope, and is represented by a faint fingerprint-like symbol on Stobie’s map.

Detail from Matthew Stobie’s Map of Roxburghshire or Tiviotdale (1770). The hill in question is the section of shading north of Thorlishope. Image: NLS.

It is absent from the map ultimately published with Douglas’s General View, whereas the nearby hills northwest of Dawstane are clearly defined on it. It was not until later in the nineteenth century that the Ordnance Survey used contours to standardise hill-sketching.

In the meantime, the status and depiction of hills varied from map to map, depending on the criteria and propensities of the mapmaker(s), or on the subjective “occular inspection� of a chain of informants. This meant that, on the maps of the Statistical Account, a hill of a certain height in one county was not necessarily a hill in another. Therefore, Sinclair’s desire for standardised surveys according to one archetypical model was necessarily thwarted.

Philip Dodds, School of Geosciences University of Edinburgh

Twitter: @PA_Dodds

We hope you have enjoyed this post: it is characteristic of the rich historical material available within the ‘Related Resources’ section of the Statistical Accounts of Scotland service. Featuring essays, maps, illustrations, correspondence, biographies of compliers, and information about Sir John Sinclair’s other works, the service provides extensive historical and bibliographical detail to supplement our full-text searchable collection of the ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Statistical Accounts.

Sources

Robert Douglas’s correspondence, quoted here, is in the National Library of Scotland: MS.3117.

![Christmas tree, from ‘Rutherfurd's Southern Counties Register... being a supplement to the almanacs; containing […] much useful information connected with the counties of Roxburgh, Berwick and Selkirk’ Published in Kelso, by J. and J.H. Rutherfurd, in 1858](https://statacc.blogs.edina.ac.uk/files/2015/12/14782967772_b57b7932e8_n.jpg)